Dispatch from Ogden

Donuts & Death & Dinosaurs

by Joe Horton

I’m looking at a dinosaur. It’s 129 days to Opening Day here in Ogden, Utah, for the Raptors. After last year’s thrilling playoff matchup, the B’s and Raptors don’t play this regular season. This dispatch is, as we say in the industry, untimely and unnecessary. More accurately, in the elegant vernacular of writers, it’s called self-indulgent and stupid. But I’m here for a family funeral; we call them celebrations of life now; my aunt has died after the long ravages of Alzheimer’s. So now you feel bad for me. I’ve got you right where I want you.

This weekend, my mom will bury her eldest sister, who has been lost to her for some time, and she will also, for the first time in her life, try a build-your-own donut bar at brunch. We will vividly remember both long after. And the dinosaur is not—you guessed it—still alive. There are life-size dino sculptures and animatronics all over George S. Eccles Dinosaur Park, and the Raptors’ Lindquist Field is also festooned with decorative raptors, some celebrating the mascot’s birth in 1994 and others the team’s 2023 Pioneer League Championship. A great writer in these Dispatches once opined from afar that Ogden’s “early history as a train hub made its 25th Street a notorious avenue of vice,” and I suppose it’s now my job to figure out if that’s still true.

“I had no idea we played Oakland,” says a Raptors fan at O-Town Eats. 25th does have some bars and clubs but also yoga and boba and brunch. This menu has vice of the beignet donut variety. My fellow bruncher continues, “I didn’t know we had any connection with Oakland really.”

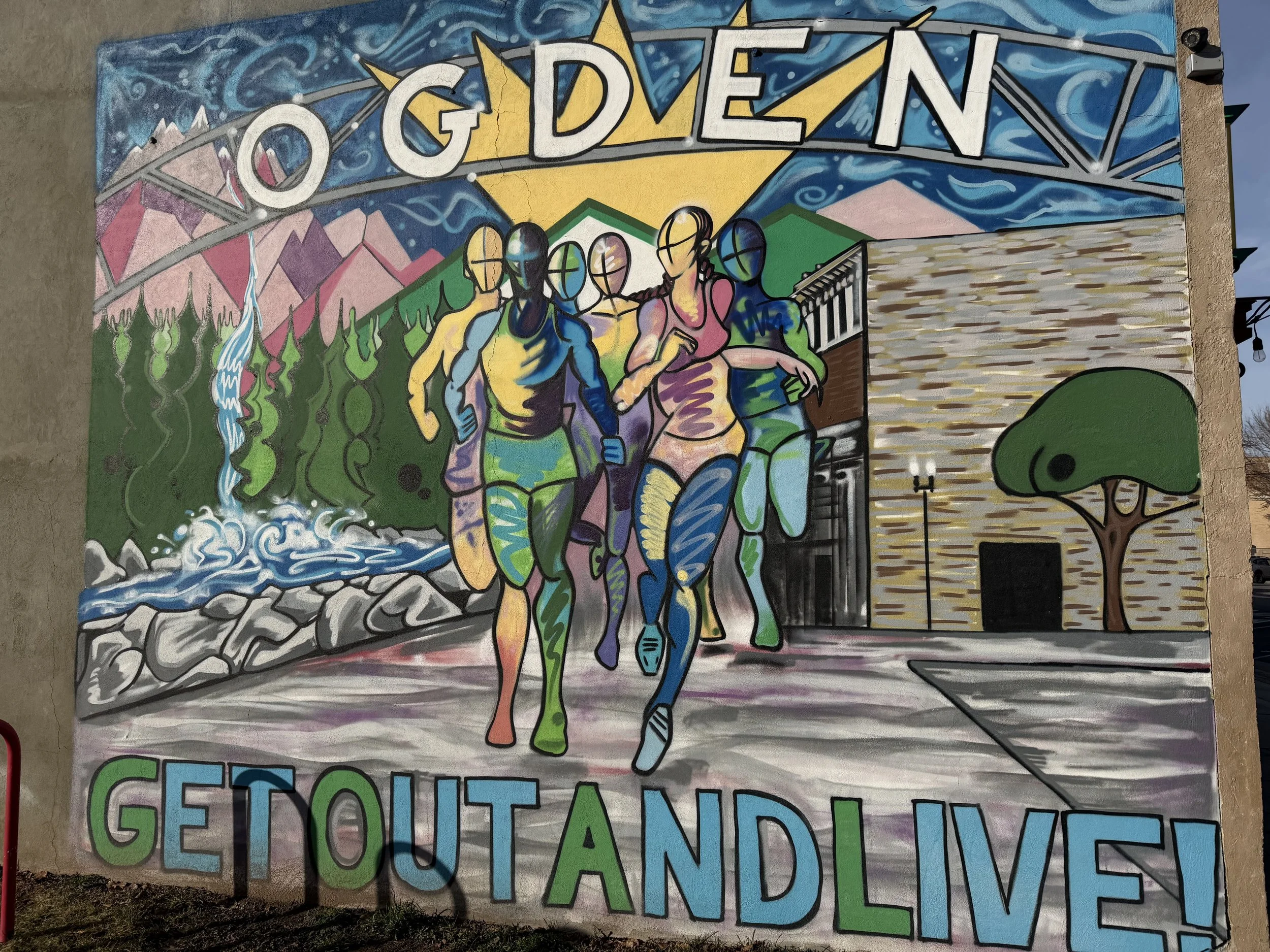

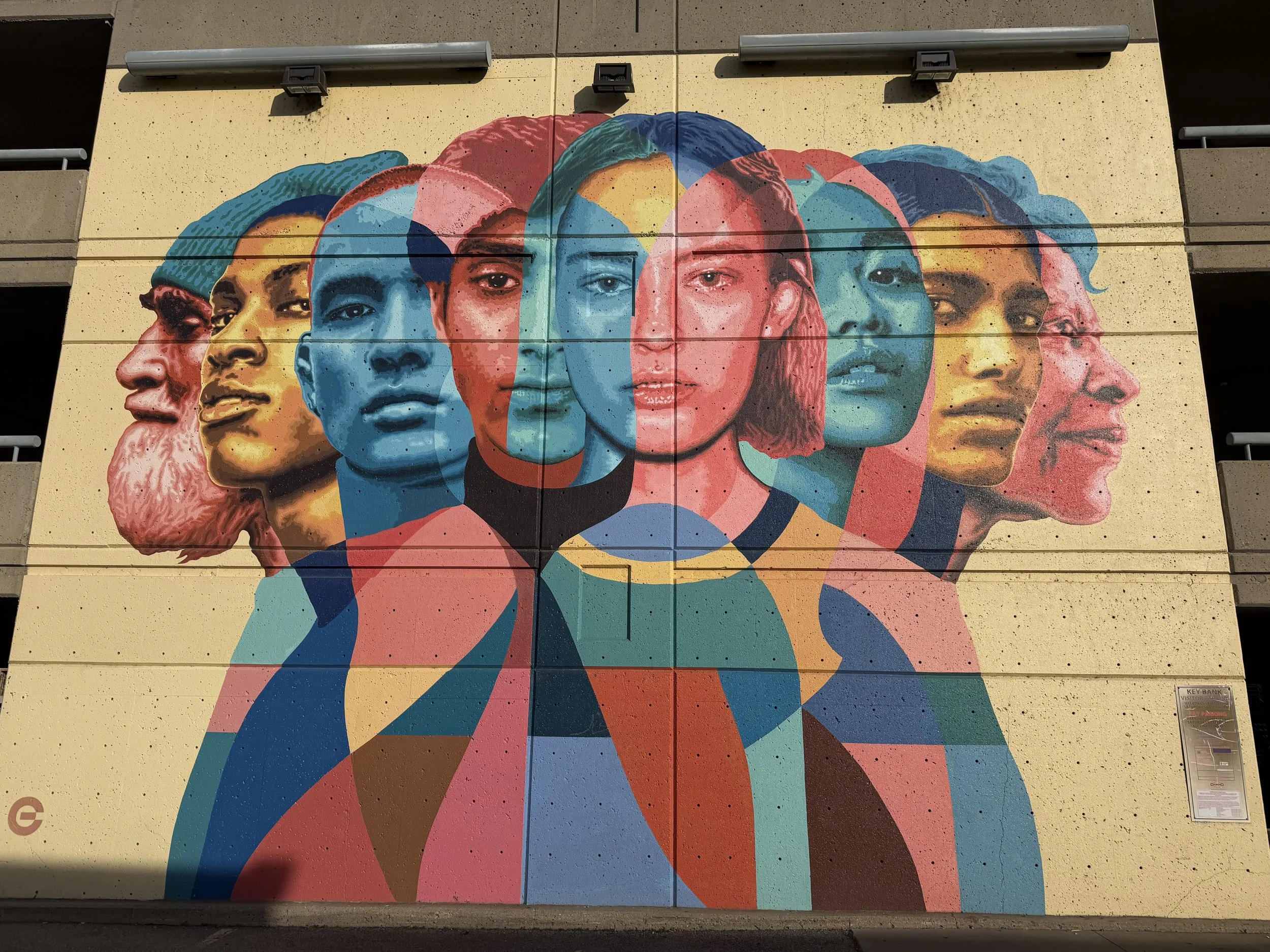

We have more in common than you’d think. Apart from celebrating recent league championships, both stadiums are near famous train stations—ours the 16th Street Station, theirs Union Station, the crucial nexus for westward travel, hence its “junction city” claims for the first transcontinental railroad—and migration and munitions vitally linked the two until the end of World War II. Both cities have contentious relationships with their nearby and better-known metropolises. Most enjoyably, both parks are surrounded by gorgeous murals by local artists and their outfields have stunning views and playgrounds for the kiddos.

One of the privileges of writing Dispatches has been learning more about the towns behind the teams we play. When I go on the road, fate is always involved. (This time, circling Salt Lake, fog kept us from landing and we made an emergency detour to Las Vegas, America’s saddest adult orphanage, for more fuel. I didn’t get off the plane for fear of incurring some kind of jet bridge resort fee, and waiting for the bathroom, a woman in the very last seat noted my B’s gear and cajoled me out of my resentment. “Oh yeah,” she said after I oh so very humbly explained my bona fides, “I read Dispatches all the time.” That, friends, is worth brief imprisonment in this maggoty desert wound.)

I never thought I’d visit Ogden any more than Idaho Falls or Marysville or Colorado Springs (again). These communities have kept baseball central to their identities for decades through good years and bad. Lindquist Field has been in the center of downtown Ogden since 1997. The Raptors, who regularly lead the league in attendance, are a beloved staple of O-Town. And today I ask anyone I meet: do you go to Raptors games? Almost everyone says yes. In fact, they sound a lot like B’s fans:

“I go all the time. Me and my dad. We go for the games but also to see all the people we know.”

“I work here right by it obviously so in the summer it feels like I’m either here or at home or at baseball.”

“I never thought I would be a baseball season ticket person but here I am, a baseball season ticket person.”

“Yeah man, baseball seems really far away but yeah I do. It’s great.”

I said almost everyone.

“Oh no, I don’t go,” says my cashier at the dino park gift shop. “But I’m a homebody, so I don’t do much of anything.”

A recent survey suggested that baseball had slipped to the fourth-most popular sport in the country, and there are those who have said for years that the game is itself a dinosaur. Too boring, too long, not enough players engaged to famous singers. Of course I walk by bars and restaurants here with every set of eyes glued to football playoffs. Three Pioneer League towns lost their teams this year. Only two cities gained new ones. Oakland knows best than even the most beloved teams are impermanent, but what their fans stitch together in their place lasts.

I’m in the alley outside the first base line between Lindquist Field’s O-Town Beach Club and playground. The diamond is quiet, the mound covered, any concessions in deep storage. The beach has gone south; this is full hibernation mode. This is in no way a dig at the Raptors—they’re a gold standard in the league. The field even offseason is one of the best in the country. But it’s 32 degrees, middle of winter, on two random days in January. This is the weekend of the Ogden Tattoo Convention. The outdoor activities I’ve seen are limited to well-bundled hiking and grumpily transporting ski equipment between unsnowy locations.

I mention it only because the odds are high and getting higher that in the multiverse, a Raptors fan visiting Raimondi as part of a Bay Area family funeral (condolences, pal) would see a field full of action. It might be a kids’ camp or little league ball or a movie night. Maybe volunteers picking up trash or planting trees or helping neighborhood cats. (Not to mention all the work across the Town, including just yesterday.) In this way, B’s baseball is a dinosaur, or at least the dinos at Eccles Park: a love doesn’t need to be live in front of you to make it inspiring.

Ah. Here I am, careening contemplative again in these pages, but at least this time, standing in the chilly and bright Wasatch range sun, it is the kaddish and the rhythmic dropping of dirt into the grave that is most to blame. During the eulogy I am uneasy; my two B’s tattoos and perhaps the small matter of not being Jewish will keep me out of this cemetery, but like any great service this invites us in. We gather closer, hold each other up. It is better to love knowing full well what we will lose than not to love, the rabbi is saying. Every person of valor’s life should not just be a blessing but a call to action. A good memory only lasts if you’re doing good with it. He makes a special point of saying that the mourner’s kaddish never mentions death. We used to call it a funeral, and now we call it a celebration of life. We hold tight our consolation and keep true our promises for the loves we cannot see.

Joe Horton is the editor of Dispatches from Raimondi.